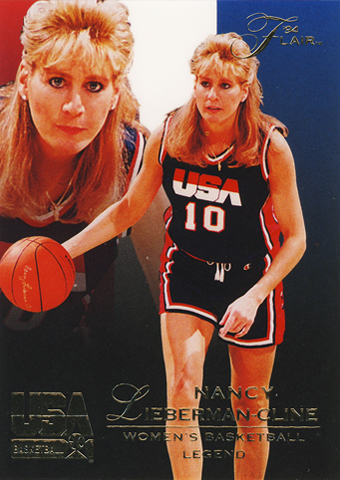

Lady Magic

We catch up with legendary Hall-of-Famer Nancy Lieberman to talk about breaking records, crossing boundaries and playing hard to make your team play harder.

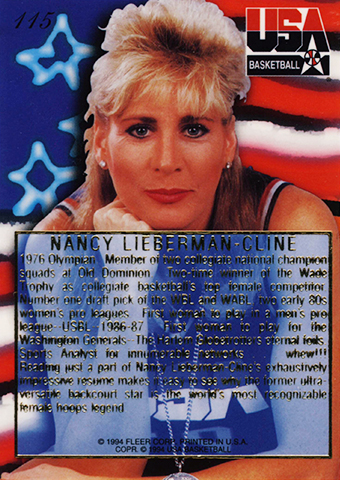

Writing about Nancy Lieberman, it’s difficult to avoid lapsing into the language of her Wikipedia entry. A Hall-of-Famer, a WNBA player, a two-time Olympian and three-time All American she has made a career of setting records. In 1986 she became the first woman ever to play in a men’s professional league. In 1997 she earned the title of the oldest woman to play in the WNBA at the age of 39, only to break this record eleven years later when she came out of retirement a second time around to sign a seven day contract with the Detroit Shock, aged 50. Off the court, she has forged a career as a broadcaster, journalist, author and motivational speaker, proving the credibility of the archetypal modern sportswoman. With a bio like that, why would you want to avoid the clichés?

Nancy moved to Far Rockaway in Queens from Brooklyn at a young age, where she was raised by a single mother. She was nine years old when she started playing football, baseball and basketball in local parks with other kids from the neighbourhood. “My mother was not very happy with me playing basketball,” she explained to me over Skype one afternoon last Autumn. “She wanted me to be that good little girl, go to school, wear dresses.” To her mother’s chagrin, by the age of 14 Nancy was taking the subway alone to Harlem to play on a court with fully grown men at Rucker Park. “I think I was a little defiant,” she says, unfazed – even as a young white girl teenager playing with adult black men in one of Manhattan’s more notorious neighbourhoods, she was secure in doing what she wanted to. Unsurprisingly she was quickly accepted among the ranks, and soon started taking her teammates home for dinner with her mother in Queens. “I just loved being out in the park.”

Figuratively speaking, proving her worth to her sceptical teammates at Rucker Park couldn’t be further away from where Nancy is today – a 56 year-old with one of the most celebrated and respected names in basketball. As we speak I become more and more aware of how she carries these formative experiences in the way she presents herself in conversation, noting her trajectory thus far. She’s proud to be a frontwoman for the sport.

And it makes sense; female sporting role models were thin on the ground when Nancy was beginning her career. “I had Walt Frazier and Willis Reed of the New York Knicks, those were my guys,” she explains. “I loved watching the NBA, I just wanted to be like Walt Frazier. But I didn’t have a lot of females when I was growing, that I would look at and say ‘wow! this is who I wanna be!’ We didn’t have lot of TV coverage of women in sports. I do remember seeing Billie Jean King playing against Bobby Riggs and thinking that was kinda cool,” she says, in reference to the 1973 tennis ‘Battle of the Sexes’, “but that was pretty much it for me until I was on the Olympic team and I started seeing other tremendous women who loved sports.” Far from bemoaning gender inequality in sports however, Nancy is proud to acknowledge how much things have changed since she was growing up. “We’re in a great time in sports for women now, because there are so many accomplished athletes out there in the major sports. It could be Ronda Rousey, it could be anybody. And it’s gonna only get better.”

In some respects, this absence of female role models seems to have played an important part in her limitless confidence. “I discovered Muhammad Ali on TV when I was about ten years old,” she explains. “He was talking about how he was the greatest of all time. I can remember just being so blown away by his confidence and his self esteem. I walked into the kitchen and up to my mother, and I was like ‘Mom, I’m the greatest of all time. I’m gonna be the champion of the world.’ She just looked at me. She was like what’s wrong with you? Why are you talking like that? and I was like ‘I’m gonna knock you out in four rounds!’ and she was like, I’m your mother! so I was like ‘two rounds! I don’t even know what I’m gonna do to my brother!’

“I put my hands on my hips and I walked out of the kitchen and I stopped and I looked at her, and I said ‘you better get used to me! I’m gonna make history!’ I don’t know why I said that. There was no Oprah or Dr. Phil, but that was what I believed.” It was only a few years later that Nancy was named to the USA Pan American team where at 16 she was a full three years younger than her fellow teammates. The following year she competed in the 1976 Olympics for the USA, taking home a silver medal, “and after the Olympics I went to college and started playing pro,” she continues. “So, I mean, I just kind of followed the path that I was asked to take.”

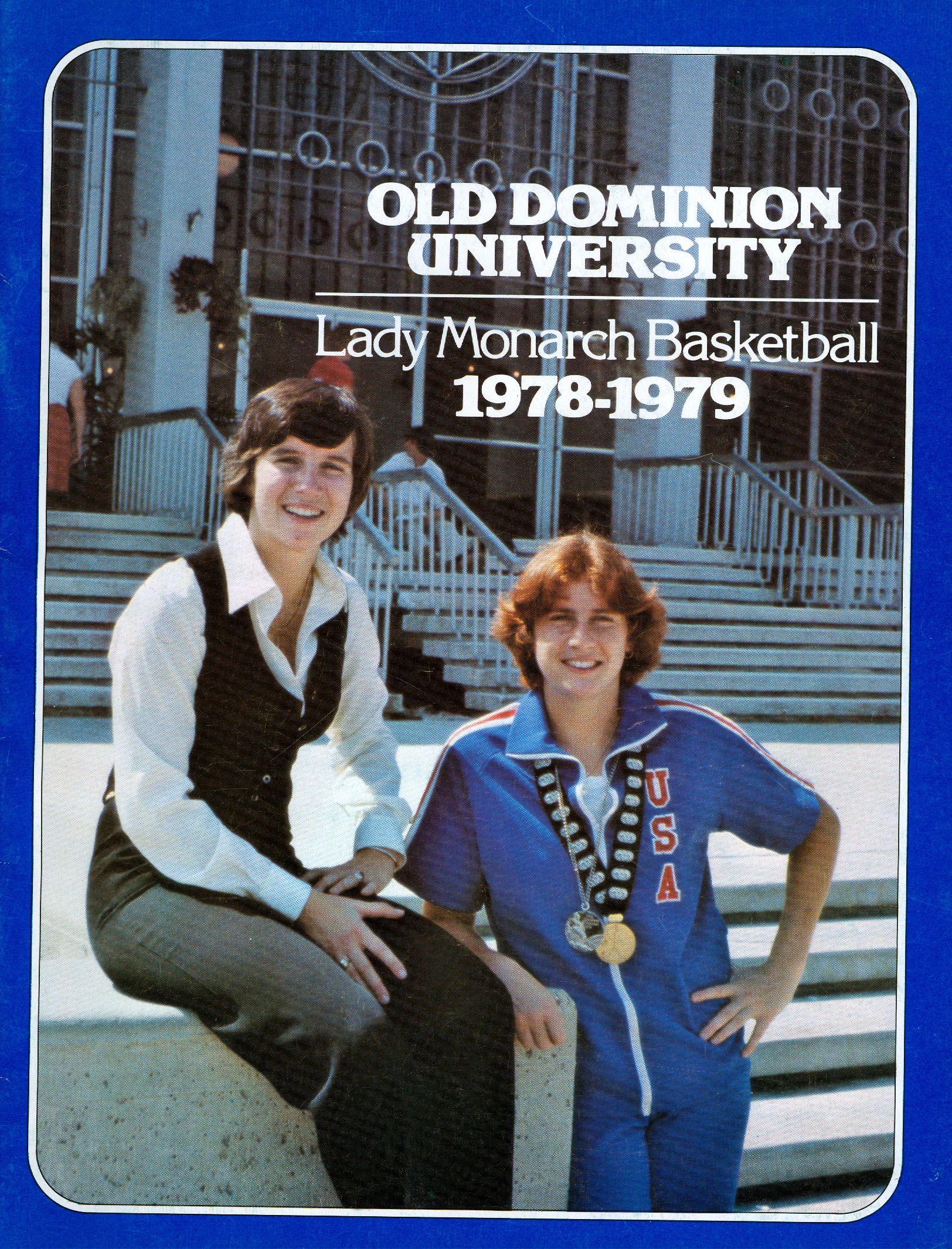

Nancy quickly became the star player on her college team at Old Dominion, but her first experience playing professionally wasn’t without its problems. “I was so used to playing against men and the physicality of the game that a lot of the girls were angry with me. They were like ‘why are you so rough? Why are you throwing elbows and being so aggressive?’ but that was the way I had been taught to play the game, by men.” There’s a note of concern in her voice, but even now she is resolutely unapologetic. “The girls thought I was trying to hurt them, but I was just trying to play hard.” How did she win her teammates over? “Well one of the questions in sport is, do you make you good, or do you make the people around you good? I think if you were my teammate you liked it, because I made you better.”

Now, almost forty years on, playing hard to make her team play harder is perhaps Nancy’s defining quality as a basketball player. In her four year career with her school team at Old Dominion she made 961 assists to a basket – a record which still stands to this day – earning herself the title of ‘Lady Magic”, a nod to Earvin ‘Magic’ Johnson, in the process. “I was around such great accomplished players as a young person that they taught me how to be in a team, and not just an individual player. It’s a process of learning not to be selfish. You learn to make the people around you better as a whole so that you can win.”

Even so, her playing style can’t fully be attributed to her teammates. “Let me tell you, whether I’ve played in men’s leagues, or women’s leagues, or Olympics, or at college, there are days when I scratch my head and go ‘how did I make that pass?’ I get such joy out of setting people up for success, passing the ball was an art form to me. I knew that I could get the crowd out of their seats with a pass if I had a little flare and flavour in my game. Women’s basketball was still very young back then, and you could just see how people gravitated towards the teams that I had played on, because we were fun to watch.”

This, as she tells me, is a trait she has passed on to her son TJ, who is a sophomore at the University of Richmond. “He wears my number ten, which I’m over the moon about. He’s a far better shooter than me, but the thing that he’s starting to connect with me on is that he’s a very gifted passer. Every time I go watch him in practice his coaches are raving about his ability to pass the ball, and to make everybody else better. And I have to tell you it makes my heart happy to know that he’s so unselfish.

“We were in the car a couple of weeks ago, and I said to him ‘TJ why do you think you’re such a great passer?’ He goes, ‘Mom, I don’t know! It’s not like I go and practise it, it’s kind of just instinctual.” And I looked at him and I said ‘honey, I never practised it either.’ I understood angles, and progressions, and where the defence was. He thinks he learned it from watching me, and how I handled the ball. And his passing is rubbing off on his teammates too. You can see it, and then you can be it.”

In 1986, Nancy Lieberman made history when she became the first woman ever to be drafted in by men’s team, playing two seasons with the Springfield Fame in the United States Basketball League. It’s an incredible achievement, but as she explains, “it wasn’t by design, it was by survival.” When two of the professional womens’ basketball leagues that she had previously competed in folded due to financial problems, she was forced to turn to a men’s league. “It didn’t matter to me if it was against men or women, I just wanted to play basketball. And that’s what I did.”

Needless to say, it wasn’t easy. “The struggle was that you could never see my true talent, because physically the guys were so much better than me. But I will say that, while you couldn’t see my talent, you could see my effort and my energy. I just had to do the best I could. I was playing against guys every day, so I had to be quicker, I had to be smarter, I had to understand the game better. And that was important to me.

“The guys were fantastic because they understood that was only there because I had to be. They respected the fact that I was willing to go out and compete against them day after day after day. That was pretty powerful for me. They were very supportive, and they pushed me to be better.” She expressed similar views to the Female Coaching Network in an interview a few years back. “If you treat yourself like an equal and do your job they will treat you like an equal,” she told her interviewer then. “So it’s my job to make it normal. I don’t go into playing in the USBL for the Lakers and go ‘oh my gosh, I’m a girl!’ No! I’m a player… It is my job to make it normal.”

This attitude was key to the period she spent coaching the Texas Legends in the NBA Development League, an affiliate of the Dallas Mavericks, in another first for women in the sport. Was it easy to transition from playing basketball to coaching, I ask? “If you love the game, the greatest thing you can ever do is play it,” she replies, with a quiet sigh of resignation. “But the second greatest thing you can do is coach. Because you’re still in the trenches. You’re still having that risk and reward.” Being the first woman to coach a mens’ team brought with it other challenges. “As a woman, I knew that what I was doing was different, and I understood that, but I wanted to also make sure that I was qualified for the job and that the kids understood how important this was,” she explains. “And I had to be ready. I had to earn their respect, and they had to earn my respect. That was very important.”

With her natural propensity to bring out the best in the people around her, coaching seems to have been a logical next step for Nancy. “When you’re a coach, you’re a teacher, and that means you’re extending yourself to somebody. And that’s what I think about every day, I want our players to know that they can be better tomorrow than they were today. What are you doing? What are you bringing to the party? Are your bringing your energy? Your effort? What are you bringing? We wanted to give them a reason to come to practice every day. We wanted to give them a reason to be better.”

Hers is the kind of belief you don’t come across very often. It’s almost forceful at times; a reminder of exactly how much self-worth is necessary if you’re going to make it as far as she has. Except she’s generous with it, too. Having moved from playing basketball to coaching, and then to broadcasting about it from the sidelines on TV, Nancy is now a motivational speaker as well as an athlete and a sports enthusiast, proving just how far the self confidence she first learned from watching Ali on the TV as a child has carried her. “You can walk by somebody and smile, and it has an effect! It doesn’t cost anything, it’s infectious. And I see it in business, I see it in sports, I see it in life. We do have the power to influence people to do things that are maybe out of their comfort zone, you know what I mean? And it feels good to know you’re helping people to be better than they thought they could be.”

“You can’t be afraid to be successful,” she continues. “There is going to be failure, but you can’t be afraid of what you can’t be. That’s something Muhammad taught me.” Without a doubt, it is this assurance in her right to do and be what and who she wants to that has propelled Nancy forwards when others have fallen by the wayside. I’d be idealistic to suggest that the societal boundaries of gender, age and race don’t exist for Nancy. Moreover she simply refuses to be limited by them. “It’s like Oprah’s vision board. I think you have to see it and say it to be it. I was like ‘I’m gonna play with NBA guys. I’m gonna play with NBA guys.’ I said it so many times that I believed it. And when it happened, I didn’t sit there in shock. It was natural to me because I had said it so many times. I was just being rewarded.”

By the time we finish the interview, I feel like I’m three feet taller. I explain to Nancy what we hope to do with Court, creating a community of basketball fans comparable to that in the US, and I’m met with a sincere wash of gratitude for our effort that proves, if the previous hour hadn’t already, just how much she loves the sport.

“Every day is a celebration,” she tells me. “We want to be able to help the game! To take our sport, our beliefs, our hard work, to the streets, to the fans. There are little girls out there who need to know that they can be who we are! They have to know that they can be a Sharapova, they can be a Torres, they can be whatever they wanna be. The more people who get to see a game, the more we’ll be able to continue to build it and grow. Time is our greatest ally.” I know better than to disagree.

Words: Maisie Skidmore